A Letter to Italian Americans Voting for Trump

I will teach my son that we have a responsibility to treat others how our ancestors should have been treated.

Introduction

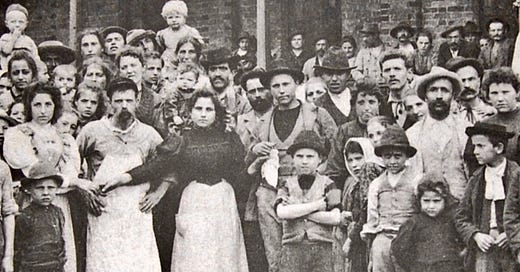

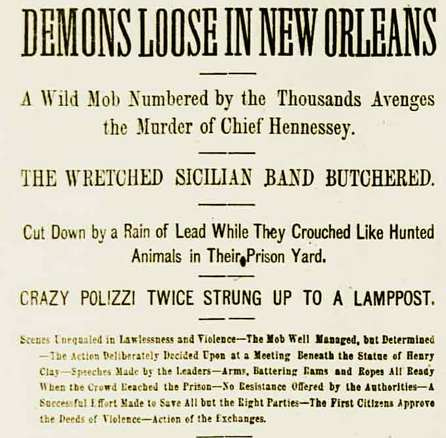

On March 16, 1891, in New Orleans, Louisiana, 11 Italian immigrants were lynched by an angry mob.

The mob believed that the men were responsible for the murder of New Orleans Police Chief David Hennessy. Just a day before the lynching, the victims had been acquitted at trial of the murder of Hennessy. Unsatisfied with the outcome, an armed mob of thousands broke into the prison to find the freshly acquitted Italians.

Once they were found, the carnage began. One of the acquitted, a mentally ill street vendor named Emmanuele Polizzi, was taken outside of the prison and hanged from a lamppost. By the time the riot had concluded, ten additional Italians had killed by the mob.

No strong evidence was ever presented to prove that the Italian immigrants were involved in the death of Chief Hennessy. In fact, the trial was filled with corruption. Lawyers for the defense were even arrested for attempting to bribe members of the jury.

Despite that lack of evidence, the eventual acquittals, and the brutal nature of the lynching, major figures and publications celebrated the bloody outcome.

“CHIEF HENNESSY AVENGED,” The New York post published after the lynchings. “NO MERCY WAS SHOWN,” The Washington Post headline read. “Vengeance Wreaked on the Cruel Slayers of Chief Hennessy.”

A March 16, 1891, editorial in The New York Times referred to the victims of the lynchings as “… sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins” and a “pest without mitigations.” ****Another newspaper argued that: “Lynch law was the only course open to the people of New Orleans. …”

John Parker, who helped organize the lynch mob, was later elected governor of Louisiana. Speaking about Italians in 1911, he said that Italians were “just a little worse than the Negro, being if anything filthier in [their] habits, lawless, and treacherous.”

Theodore Roosevelt, just three years before becoming President of the United States, suggested the lynching was “a rather good thing.”

After much pressure in the run-up to his 1892 reelection, President Benjamin Harrison eventually denounced the lynching in a speech to Congress. He also agreed to pay a restitution of over $2,000 ($70,000 adjusted for inflation) to the families of each of the victims. To further ease tensions with the Italian government and Italian-American voters, Harrison designated October 12, 1892 as the first “Columbus Day.”

Old Dog, Same Tricks

What does any of this have to do with the current political moment? Through assimilation and the passage of time, Italian-Americans no longer face serious discrimination. But the immigrant experience continues. In many critical ways - it’s largely unchanged.

As such, I am endlessly fixated on a connection between our current political moment and our nation’s historical treatment of immigrants.

It’s a fitting focus when analyzing the Trump movement since Trump launched his bid for the White House on June 16, 2015, with a speech that included these remarks about Mexican immigrants:

“When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending their best…They're sending people that have lots of problems, and they're bringing those problems with us. They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

I would only learn later how similar this was to rhetoric used against Italian-American immigrants in the early 20th century. But even then, as a young, politically naive 20-year-old, his language shocked me. In my mind, politicians were supposed to be dignified. If and when they had ugly thoughts, they would always first water them down to avoid ruffling feathers. They’d offer something softer instead like: “It’s not that we believe that immigrants are criminals. But we need to take care of Americans before taking in anyone else.”

But here was Donald Trump, laying the foundation for a campaign for President of the United States, skipping over the linguistic sanitation that I had come to expect. According to Trump, Mexican immigrants were “rapists” and only “some” of them were “good people.”

But he didn’t stop there. In December 2015, Trump took it a step further when he argued that members of the world’s second largest religion should be prevented entry to the United States: America needed “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country's representatives can figure out what is going on,” he said. (Little did I know at the time that this proposal would effectively become law when President Trump signed Executive Order 13769 into law in January 2017).

In October 2016, just weeks before the election, I, then still a self-identifying conservative, submitted the following condemnation of Donald Trump to my college’s alumni magazine in support of my pitch for voting for a third-party candidate:

“[Trump] has made disparaging comments about women, Hispanics and Muslims…It’s still hard to understand, but the more insensitive Trump becomes, the more it animates his base.”

To my half-hearted dismay, Trump won the 2016 election. My concerns about his character were genuine and I didn’t want him to win, but I had somehow convinced myself that he was a better alternative to his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton.

January 6, 2021 and the run up to it should have been the end of Donald Trump’s tenure as a political leader. But it wasn’t. The Republican Party selected Donald Trump as their party’s nominee for president in 2024.

In other words, little has changed. What has changed - for the worse - is Trump’s rhetoric about immigrants. What started in 2015 as straightforward fear-mongering about violent crime has transformed into sermons about the how immigrant “blood” ruins the purity of the United States. In December 2023, Trump told a New Hampshire crowd that all undocumented immigrants are “poisoning” the “blood” of the country:

“They let — I think the real number is 15, 16 million people into our country. When they do that, we got a lot of work to do. They’re poisoning the blood of our country…That’s what they’ve done. They poison mental institutions and prisons all over the world, not just in South America, not just to three or four countries that we think about, but all over the world. They’re coming into our country from Africa, from Asia, all over the world.”

The Data: Italian-Americans Love Donald Trump

There is no hiding the fact that Italian-Americans overwhelmingly support Donald Trump and the Republican Party. A recent poll from New Jersey found that Italian-Americans, as a group, are significantly more Republican than the state as a whole.

Italian-American men are particularly fond of Trump: “While Italian American women are no more or less likely to say that they supported Trump than other white women in [New Jersey], Italian American men are more likely to say that they supported Trump (59 percent) than other white men (45 percent).

The question is…why?

The Only Difference Between Us and Them Is…Time.

The 1891 New Orleans lynchings were but just one moment in a larger pattern of discrimination against Italian immigrants that continued into the 20th century.

Italian immigrants were often considered by employers as a source of cheap labor. As a result, many worked in dangerous and low-paying jobs, such as in construction, mining, and factories. They were exploited by employers, paid less than other workers, and faced hostility from labor unions that saw them as strikebreakers or competition for jobs.

Italian Americans were often considered racially inferior by Anglo-Americans. They were stereotyped as inherently violent, criminal, or lazy. Media portrayals didn’t help either. Italians were portrayed in film and culture as mafiosos or anarchists, which reinforced negative perceptions and social exclusion.

Like most immigrant groups, Italians were segregated into ethnic enclaves, giving rise to "Little Italy" neighborhoods, due to both social pressures and economic necessity. They faced restrictions in housing and were excluded from certain schools, clubs, and neighborhoods.

Due to concerns about demographic change, two congressmen proposed a bill that specifically aimed to restrict the influx of Southern and Eastern European immigrants, including Italians. The Immigration Act of 1924 was passed into law with support from both the American public and nativist groups like the Ku Klux Klan. The bill set quotas that strictly limited the number of Italians allowed to enter the country.

The congressmen behind the bill pitched the act as a way to prevent "a stream of alien blood” from entering the country. In 1928, Adolph Hitler praised the American bill, arguing that it effectively kept out “strangers of the blood.”

Does that rhetoric sound familiar?

It should sound familiar. Human beings might be complex. But we, as a group acting over time, are creatures of habit. We are prone to patterned behavior. Donald Trump did not invent harsh rhetoric about immigrants. He’s echoing the prejudices that humans have exhibited against each other across time.

History has already harshly judged the leaders that have used their positions of authority to attack the most vulnerable.

It’s time to ask if we are standing on the right side of history.

Due to assimilation and the passage of time, Italian Americans no longer face serious discrimination in the United States. But this means that we have an even greater responsibility to stand up for those groups that now face the type of discrimination that our ancestors faced. The first step is to recognize it when it occurs.

If you are an Italian American that loves our people and our history, it is your duty to ensure that no other group is subject to the type of rhetoric that reduces an entire people to violent conduct of a select few. History shows us that it is exactly that type of rhetoric that leads to bias, prejudice, discrimination. At worst, it leads to violent tragedies like the New Orleans lynchings.

After all, the only difference between our ancestors and the immigrants crossing the border today is…time.

What about immigrants that commit violent crime?

“But Tom,” you might say, “Trump doesn’t hate immigrants. Donald Trump is only talking about immigrants that commit violent crime.”

My first reaction to this claim is that the Biden/Harris administration oversaw an increase in border confrontations and a decrease in violent crime. This year, the Biden/Harris administration will oversee more border removals than the Trump administration did in any of their pre-COVID years. Violent crime is also down.

But let’s get back to Donald Trump: his remark that all undocumented immigrants poison the blood of American should dispel any claim that Trump is strictly worried about reducing violence.

But even if we assume that Trump is strictly interested in reducing violent crime, his rhetoric is still needlessly inflammatory.

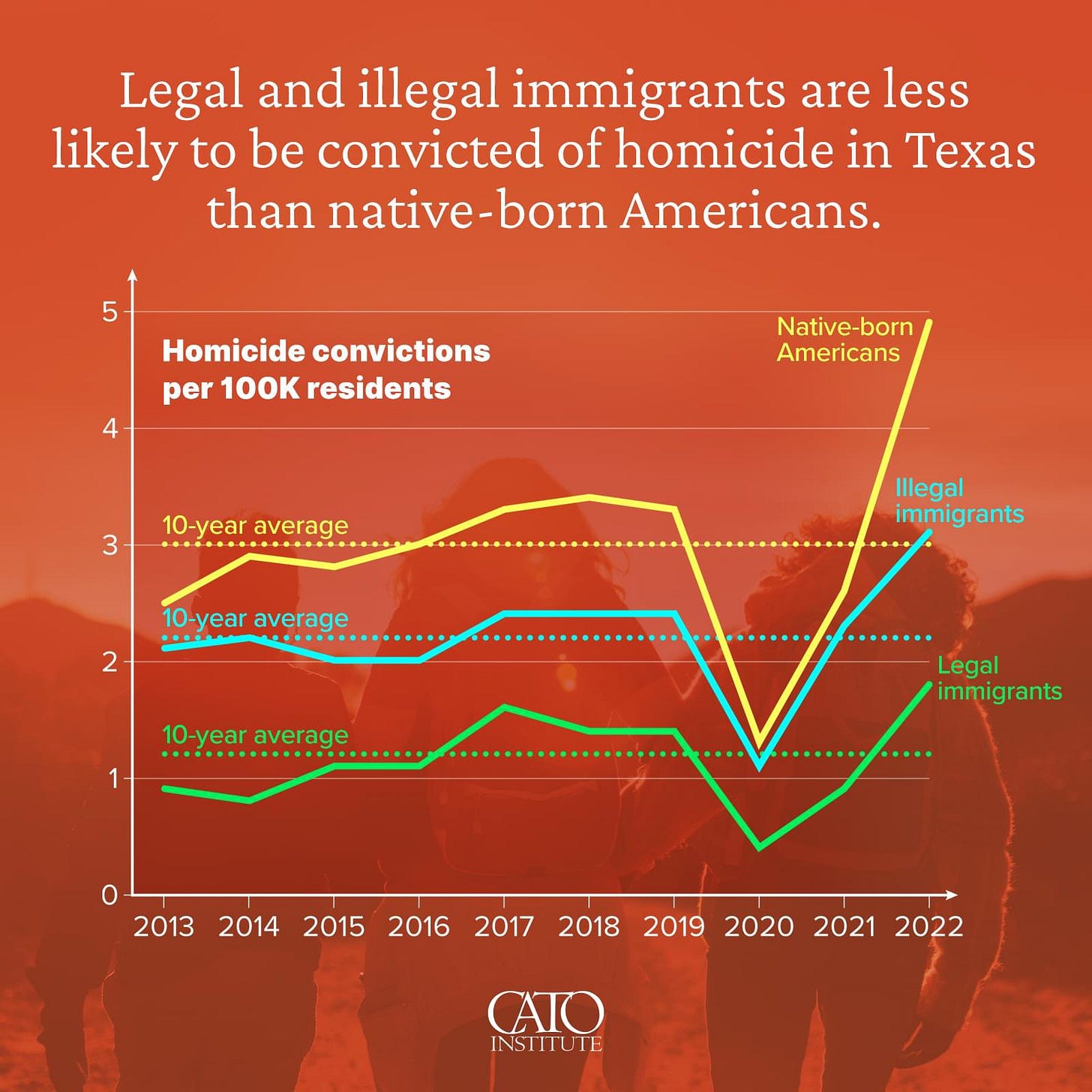

Immigrants commit crimes. Some immigrants commit violent crimes. But the immigration status of a criminal is only relevant in our national discourse if we can prove that immigrants are committing more (or many more) crimes than native-born Americans.

If it’s true that immigrants are just as likely (or even LESS likely) to commit crimes than native-born Americans, then Trump’s rhetoric serves no purpose at all other than to flame anxieties about a non-existent immigrant crime problem.

Right? Right!?

The reality is that multiple studies have proven that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than native born Americans. (Here are some studies from varied sources: one, two, three, four, and five).

If your position is that even a single crime committed by an immigrant is too many or that we should exclude any group of people from this country if any single member of that group commits a crime on American soil, then pack your bags. By your standards, your ancestors would not have been permitted to enter this country either.

Treat Others How Our Ancestors Should Have Been Treated

In 2019, 128 years after the lynchings, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell apologized to Italian-Americans for the lynchings.

“What happened to those 11 Italians, it was wrong, and the city owes them and their descendants a formal apology” Cantrell said in an address. “At this late date, we cannot give justice. But we can be intentional and deliberate about what we do going forward.”

“This attack was an act of anti-immigrant violence,” Cantrell continued. “New Orleans is a welcoming city … But there remain serious and dark chapters to our shared story that remain untold and unaccounted for.”

“This is not something that’s too little, too late,” one Italian-American told a reporter before Cantrell’s speech. “This is something that has to be addressed.”

It’s never too late to do the right thing.

I was moved by the words of a community member that spoke up at a board meeting in Staten Island, New York, during a discussion about housing migrants in their community:

“Staten Island has always been a proud Borough and one that has always helped it’s own. And they think the divisive issue here is that we do not see these migrants as our own. I'm a fourth generation Staten Islander and my family they came over here in 1910. I want each and every one of you to ask yourselves what year your family came to Staten Island. Staten Island has always been made up of migrants We're proud to be Italian on St Joseph's day when we get our pastries and we are proud to be Irish during the Forest Avenue parade. Yet we have forgotten this and have put the blame on people who are just looking for a better life. People like every single one of our ancestors. Go back to the stories that we grew up with of times where newspaper articles reported “the Irish are stealing our jobs” or the times when signs read “No Guineas Allowed. ‘Think back to those stories. Our ancestors have been subjected to the same hate that was displayed at St John Villa a few weeks ago. The difference now, the sad difference now, is that the bullies are the children of immigrants. If you wouldn't say ‘go back to your country’ to your Nona, you should ask yourself why you are so willing to say it to a black and brown person.”

I have a one-year-old Italian American son. I will teach him that that his life is the product of the sacrifice of those that came before us. His life is a product of his ancestor’s perseverance in the face of discrimination - the same type of discrimination that immigrants face in the 21st century as a consequence of Donald Trump’s rhetoric.

My son will understand that the mere act of his ancestors stepping off the boat inspired the same type of economic and security anxieties that Americans feel today. He will, I hope, understand that the only difference between the family crossing the border tomorrow and his own family is…time.

He will, I hope, use that understanding to shape how he views the families coming here for a better life.

Perhaps a slight variation on the “golden rule” is appropriate here: “treat others how your ancestors should have been treated.”

You can stand up for your ancestors by standing up for immigrants today. You can try it by voting for Kamala Harris in November.